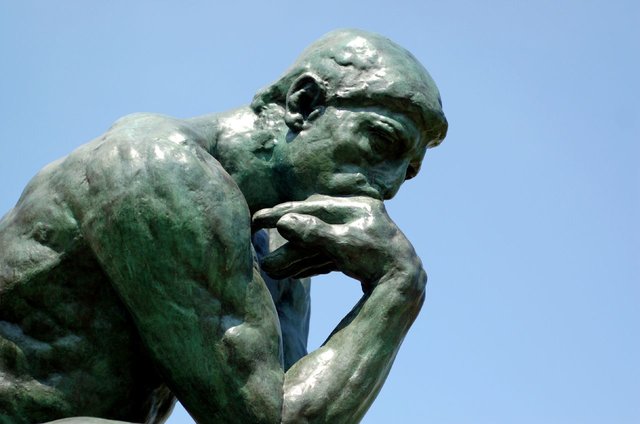

Thoughts are powerful. Without the power of thinking, we would not progress as a society. We would lack innovation and creativity. We would not enjoy the advent of new technology and the benefits of such. However, sometimes “thinking” can get us into trouble. But the reason why may not be the reason you “think.”

The reason is that, tragically, in my opinion, many people believe “thoughts” to be things that really aren’t at all proper thoughts. To demonstrate, I’ll provide two different examples of “thoughts” to allow you to distinguish between the two:

Example 1: “I think that the most efficient way to communicate with others is to enter their information into a mailing list database, whereas I can send them all communication at one time with the click of a button.”

Example 2: “I think that she is trying to be efficient because she is sending me communication through a mailing list database.”

So, which “thought,” of the two given examples above, is a proper thought?

If you picked the first example, then you and I are in agreement. And here’s why — The first “thought” is a reflection; it’s an observation. It’s a reflection of our reflections. It’s internal. It may be the result of deliberation and experiences and the sum of many different experiences that lead to the formulation of an idea about something. That is what I would deem a “proper” thought.

The reason why I do not agree that the second example is a proper “thought” is because the use of the term “think” in that second example is not a reflection or an observation, even though it may appear to be such. In my opinion, the term “think” is rather an interpretation, or judgment, or analysis of another’s behavior.

Just because you “think” she is trying to be more efficient, you only have the facts available at your disposal, which is that you are receiving email from her through a mailing list. The rationale behind the observable act is anyone’s guess, with exception to the person who is sending emails through that database.

Now, if you were to ask her person why she is sending emails through the mailing list, and she tells you that she is doing it because she wishes to be more efficient, then you have your answer. But until you know the facts of the situation, all you have is speculation, conjecture, opinion, judgment, analysis, guesswork, hunches, hypotheses, stabs in the dark, and supposition.

This brings me to the point I am trying to bring across to you today: I advise you to be cautious about what you “think” are “thoughts” that really aren’t proper thoughts at all, because they can end up causing more problems than you’d prefer. Or, perhaps you’ve already been using them and are trying to figure out why you’re suffering and things aren’t quite as wonderful as you’d like.

Either way, I recommend you give some time to reflect upon what is really a “thought” before you start telling people what you “think.” Unfortunately, in my opinion, we’ve been conditioned to freely interchange one type of “thought” with the other type of “thought.” When we tell people we’re “thinking,” what we’re really telling them is how we are interpreting the actions of others.

How can you tell which is which? Here’s a very easy way to discern between the two — ask yourself what comes after the word “think.”

If the word “he,” “she,” “they,” or “you” follows the word “think,” chances are it’s an interpretation, diagnosis, judgment, and speculation. This will likely land you in the land of debate and argument and discord.

For example, if you say to someone, “I think that you are being unreasonable,” what do you think your chances are of the other person saying (sincerely), “You’re right. I’m being completely unreasonable! Wow. Boy, did I make a mistake. My apologies!” I’ll put it this way: don’t hold your breath waiting for that type of sincere response.

The reason why you won’t get that type of response is because you interpreted and diagnosed the motives behind the observable act that took place. Before you jump into saying “you’re being unreasonable,” back up and figure out what “unreasonable” looks like. What actually happened that led to your diagnosis of such? That’s where the conversation needs to start, in my opinion.

So, what are you thinking? Are you disguising judgment and diagnosis as a thought? Or, are you truly and authentically reflecting and contemplating internally? Take some time to properly “think” about it, and take some more time to “think” before you tell other people what you “think,” and I “think” you’ll be in a much better place as a result.

Photo: https://www.flickr.com/photos/seatbelt67/502255276